Note: This is the first version (v1) of an essay-manifesto in progress.1

Table of Contents

I. Honoring our human journey

As I’ve talked so far about the Contemplarium, I’ve been groping around for a word to describe what I really care about, what my work is meant to do. So far, I’ve been calling my aim “meeting moral-existential needs.” That’s kind of a mouthful to gesture at something I find so important and feel so viscerally—yet find so incredibly difficult to nail down in words.

But recently, I think I’ve finally pinpointed what I’m getting at. It boils down to a simple human activity:

Honoring.

In particular, I care about those moments where we honor our human experiences.2 That is, when we regard and treat people’s experiences of life with the respect and care they deserve. Honoring someone’s joy with celebration. Honoring someone’s grief with mourning. Honoring someone’s uncertainty with care.

And doing this not because it will fix or change anything, but simply because we feel those people and their experience are owed it.

I think we see this kind of honoring in our everyday lives:

When a friend loses someone they love, you send your condolences. Not because it will bring that person back, nor because you expect your impossibly inadequate words to lessen the pain, but simply because your friend’s loss calls for some kind of acknowledgment and respect. It calls for honoring.

When a colleague you admire gets a promotion, you give them your congratulations. Not because it will score you social points (though it may), nor because they necessarily need to hear it a million times, but because your colleague’s achievement calls for celebration. It calls for honoring.

When you realize you’ve hurt a loved one, you might offer an apology. Not because it changes anything that happened in the past, nor because you should expect forgiveness to result from it (though it might open the door), but because your loved one’s pain calls for your acknowledgement and ownership of responsibility. It calls for honoring.

We are also called to honor bigger life milestones: someone passing into adulthood, someone experiencing sickness or the passage to death, someone entering into a committed relationship. We honor smaller moments too: perhaps honoring your own feeling of wonder by kneeling to the ground, or honoring a feeling of yearning with a quietly uttered wish. Taken together, these experiences large and small add up to what I call our human journey.

These moments mean so much because they represent occasions to honor the equal and inherent dignity we can’t help but to see in human beings. As humans, we have this primordial compulsion to recognize a human being’s experiencing3 as worthy, as important, as something to be in mutual relationship with. By virtue of this moral weight we accord to that subject’s experiencing, we are pulled to bear witness to it, to owe it respect and care, to treat it through our speech or action with the dignity it deserves. Honoring our human journey discharges this primordial compulsion—and in so doing realizes, in a strange and powerful way, a fundamental piece of our humanity.45

II. Our lost honoring infrastructure

Having put a finger on it, I can see the compulsion to honor our human journey infuse most aspects of our lives. As long as we are surrounded by beings who experience life—and are such beings ourselves—we find ourselves pulled to care about that journey and how we ought to honor the moments within it.

But oddly, I find it’s not something we really know how to talk about. Or do well.

Mostly, we kind of stumble our way through how to honor our human journey. Yes, part of this is simply the nature of honoring. It is infinitely contextual and complex— just as it should be, because it responds to our infinitely diverse experiences. Honoring will always have an intrinsically messy and improvisational dimension.

But I think there’s another thing going on, namely:

We’ve lost our honoring infrastructure.6

By this I’m referring to the institutions, tools (or technologies), and skills that support our practice of honoring. I think we’ve lost much of these over the last stretch of modernity—or at least lost access to an honoring infrastructure that is authentic and accessible to most of us—leaving us to fend for ourselves.

To illustrate what I mean, consider a life milestone that human societies have long felt the need to honor: a baby’s official entry into life and into society.7

Imagine the ancient Roman baby dedication ceremony—the dies lustricus. In this ceremony, a new baby would be purified and given a name on the eighth or ninth day of life, and the family would celebrate with a feast.

As straightforward as this ceremony was, it was supported by the extensive honoring infrastructure that underlay ancient Roman society. For example, several institutions supported this particular honoring practice: the deeply rooted Roman family, the institutions of Roman religion that nurtured veneration of the childhood goddess who was said to preside over the event, and the Roman legal institutions that imparted legal meaning onto the rite of passage. There were tools that supported the honoring practice: the physical artefacts involved in the purification ritual, and also liturgical “equipment” in the form of what words to say and actions to take. And there were skills that supported the honoring practice: most evidently, facility with the ceremony, or the ritual know-how and presence that passed down from generation to generation in the family.

Later, the pagan dies lustricus gave way to Christian baptism as the emergent Catholic Church displaced the family as the primary institution undergirding this honoring practice. The Catholic Church involved different technologies for baptism: for example, the newly developed space-making technology called a “church” and its baptismal font (rather than the home), an increasingly standardized liturgical script, and new artefacts such as candles, crosses, and Bibles. The skills involved in operating those technologies also became monopolized by priests, who coupled literacy, liturgical fluency, and pastoral skill in a reinvented profession.

As the West8 fragmented religiously after the Protestant Reformation and then secularized over the past few centuries, the honoring infrastructure provided by the Christian monoculture has given way to an honoring patchwork. Here in the more secular city of San Francisco, for example, the honoring practice of baby dedication is mainly supported by two fragmented kinds of institutions today: (1) religious communities who maintain the practice privately, mostly for their own members, and (2) private families or groups maintaining (or inventing) a baby dedication tradition, sometimes with the support of cultural institutions.

Neither of these options seem fully satisfactory, not only for baby dedications but for all the ways we might honor our human journey. The first option allows us to enjoy the localized private honoring infrastructure of religious institutions, but it usually asks us to become members of the faith—coupling theological commitments and membership requirements with honoring practices in a “package deal”. But a lot of us seeking honoring aren’t looking for faith identity. Some of us bite the bullet on religious ideology and membership because we know the honoring infrastructure is so valuable, but we are left with the burden of intellectual incongruence.

The second option asks us to go it alone in our private families or groups. This provides wonderful latitude for creativity and personalization, but the tradeoff is that it puts all the onus on private individuals or groups to rebuild the honoring infrastructure over and over again, left to tenuously inherited family traditions or self-help books and blogs to fashion new rituals and pick up unfamiliar skills every time. As excited as we may be about the opportunity for invention, what ends up happening, frankly, is that most of us usually skip honoring. For ourselves and those around us, small moments and life transitions pass without any recognition. We accrue an honoring deficit that never gets paid.

III. Honoring as a polity

With the fragmentation of our honoring infrastructure, we’re left with another unfilled vacuum. Not only do we no longer support honoring for people qua private individuals and groups, but we also no longer support honoring for people qua local polities—e.g. as local neighborhoods, towns, or cities. Some of the examples above considered the honoring that happens among family, friends, colleagues, or loved ones. But we also owe honoring for each other as neighbors and citizens—strangers with whom we simply share our local polity. We need to honor as a polity.

Societies preceding us maintained ample honoring infrastructure that served the local polity as a whole. Roman society was saturated with temples utilized across social strata to honor the many dimensions of life (through representations as gods), and a calendar of public feasts and festivals brought communities to honor key moments of the human journey together. Later, Catholic clergy stewarded the public honoring practices within the bounds of their assigned parishes, with the Catholic mass in particular bringing the polity together on a weekly basis to honor the sharedness of their human journeys. In New England, governed by the Congregationalist tradition9, parish meetinghouses served as the honoring center for the entire town. Crucial moments of the human journey were honored by the entire community.

But over the last few centuries, the infrastructure that facilitated honoring the human journey among neighbors and fellow citizens has receded.

Part of this is a good thing, because the reality is that in historical Rome, Catholic Europe, and New England, these polity-oriented honoring infrastructures were deeply entangled with the state, if not run and administered by it. For many reasons, honoring infrastructures should rightly be separated from coercive state power10, and in the Christonormative West11, this is what happened with the well-justified separation of church and state.

But what has resulted is that we’ve thrown out the baby with the bathwater. In rejecting the state-backed church, we also lost the common honoring infrastructure that allowed us to honor as a polity. Perhaps if there were a hypothetical separation of “temple” and state in ancient Rome, the result might have been different: Because Roman religion focused more on shared practice rather than adherence to a creed or identity, we might have retained a non-state honoring infrastructure that broadly served the public as an acceptable, voluntary common denominator outside of state power.

Of course, our separation of church and state happened in Christendom, so we got a different result. Religion in the Christonormative West uniquely bundles theological creed and membership identity with honoring practices. So when Western religion was divorced from the state and fractured along theological lines after the Protestant Reformation, the honoring infrastructure had to fracture with it. Walled-off congregations now honor the human journey separately, and each version of practice is so laden with theological idiosyncrasies that no one tradition can legitimately lay claim as an acceptable common denominator in the civic square.

As a result, we have an attenuated honoring infrastructure as a polity. We have some ceremonies and traditions associated with civic life, such as parades on public holidays, interfaith services, and state funerals.12 But that’s a far cry from the rich honoring life I think a polity deserves.

But wait—you might ask at this point—What do you mean by “deserve”? In a contemporary liberal society, removed from the context of these preceding societies, what honoring do neighbors and citizens still really owe each other?

After all, in historical Christendom, it was Christian concepts—like the body of the church as a manifestation of the body of Christ, or the story of Jesus’s life as a template for reckoning our own human journeys—that ostensibly provided the basis for caring about polity-oriented honoring practices like the Eucharist and Christian liturgical calendar. For centuries, it was Christianity that offered the West the theological rationalization for honoring each other’s journeys as a body civic. From this history, we might assume that religion gives us the only available justification for polity-oriented honoring. Now that we are in a post-Christian society, what justification is left? Must we still think neighbors and citizens really owe any honoring to each other?

I think we find an answer to this question in the project that currently governs our societal order: Liberalism.13

At the heart of the liberal project—and by this I mean that central animating intellectual force that has shaped our society since the Enlightenment—is the revolutionary belief in the inherent and equal moral dignity of every human being.1415 A well-ordered society or polity is organized in such a way that this moral dignity is honored.

Over the last few centuries, the liberal project has been fantastically productive in trying to enact this belief in the political sphere. We’ve fashioned institutions of democracy to offer every morally equal individual a say in the decisions that affect our lives, and we’ve devised systems of rights to protect every individual against treatment that violates our equal and inherent moral dignity. From voting booths to city halls, from public schools to the jury box, the foundational political structures that govern our liberal society are thoroughly a product of the ambitious liberal project to honor the equal and inherent moral dignity of every human being.

But there’s something this liberal project has missed or at least underemphasized16, at least so far: A well-ordered society of moral equals entails the honoring of that moral dignity not just in the political sphere, but also in the interpersonal sphere17 as well. The core of the notion of moral dignity is that we recognize each other as equal persons, as moral agents, as subjects with experiences rather than as objects. So yes, this means that we honor each others’ personhood by building the political structures that respect it, but to really take moral dignity seriously, this also means that we honor each others’ personhood by honoring each others’ experiences—a recognition of the subject-to-subject relationship we are committed to. In other words, people in a society of moral equals relate to each other not merely by governing each other as policy objects, but also by honoring each other’s experiences as people.

If we take the moral essence of liberalism seriously, and are truly serious about realizing the liberal project—and I think we ought to be—it becomes clear that we as neighbors and citizens do still owe a form of honoring to each other, absent any religious motivations. This honoring enacts our commitment to our equal and inherent moral dignity, to treat each others’ experiences—our human journey—with the respect and care they deserve. It is true that we can’t and shouldn’t legislate it or use the coercive power of the state to enforce it. But we can and should—as a polity, as a people voluntarily doing so—build the honoring infrastructure to support it.18

IV. A people who honor

So we have two things missing: (1) As private individuals and groups, we lack the support to honor the human journeys of those with whom we have private relationships, and (2) As a polity, we lack the support to honor the human journeys of our fellow polity members.

What would it look like, instead, if we supported the honoring in our society in these two ways?

What if, instead of skipping the honoring owed to our most human experiences because we didn’t have the occasion, the time, or the support—what if we all had access to people and tools to help us make it easier? What if, instead of swallowing compromises to our intellectual integrity, we had an honoring infrastructure that offered beauty, depth, and tradition alongside authenticity of mind and spirit?

What if, for many of the profound experiences we share as communities—like the thousands who died in any given city during Covid, or the suffering of those living on our streets—what if instead of pretending these didn’t call for a moment of communal honoring, we took the time to treat these experiences what the moment of care that they are owed?

What if, instead of a polity who had lost the muscles to commemorate our lives together, we were a polity whose strength lie in our capacity to truly see each other as people?

What if, instead of a people who forgot or overlooked our human experience, we were a people who made space for it?

What if, in short, we were a people who honor?

V. A common honoring infrastructure—that is legitimate

To my mind, becoming a “people who honor” calls for building a common honoring infrastructure. This honoring infrastructure is “common”19 in two senses:

First, it’s common in that it’s available to serve anyone in our polity. A common honoring infrastructure is meant to support any individual or group in private honoring, as well as the polity at large for public honoring. It is not just for those who subscribe to certain beliefs or membership identities, particularly religious or spiritual ones.20

Second, it’s common in that it belongs to us all. We think of certain institutions (e.g. museums, symphonies, libraries, parks, hospitals, utilities), technologies (e.g. open-source code, the Internet), and skills (e.g. dancing, cooking, storytelling) as in some sense belonging to our culture or our public at large. In the same way, a common honoring infrastructure belongs to us all, and so should be shared and treated accordingly.

In talking about building a common honoring infrastructure, you might imagine a return to ones we might have had in the past. But in a liberal society—as ours rightly strives to be—we can’t simply recreate, say, the common honoring infrastructure of ancient Rome, or the one in historic Catholic Europe.21 For a common honoring infrastructure to be legitimate in our liberal order, it must operate within key parameters that derive from the central liberal concern for equal human dignity. Some of these include being voluntary (i.e. autonomy-respecting), pluralistic (in a way that respects dignity), and democratic:22

(1) Voluntariness (Respect for Autonomy) — This seems almost so obvious in a society with the formal separation of church and state that it hardly needs explaining: people shouldn’t be compelled by coercive state power to participate in an honoring infrastructure, as happened in, say, historic Catholic Europe. To do so would violate the autonomy due to moral equals to choose how or even whether to honor, and so run counter to the liberal impetus of this project in the first place. But I think it’s worth repeating in light of some alarming proposals for, essentially, a return to theocracy23—proposals which are in some ways motivated by similar concerns to the ones I’ve presented here, yet come to vastly different and mistaken conclusions. So I want to make myself very clear: theocracy runs counter to the very purpose of this project. (Additionally, it is worth being careful about other, less obvious ways in which an honoring infrastructure might threaten autonomy.24)

(2) Dignity-Respecting Pluralism — For an honoring infrastructure that works for everyone and belongs to everyone, it has to be compatible with the wide variety of theologies and values that a polity may hold—of course, within the constraint that those theologies and values are not inconsistent with the central liberal concern for equal human dignity. So a common honoring infrastructure will be spacious, serving people’s honoring needs effectively regardless of what they believe about God, the universe, and other ultimate concerns, while rejecting disempowering or demeaning theologies or elements of those theologies. Additionally, the common honoring infrastructure should equally welcome people who happen to belong to private honoring infrastructures (e.g. “I’m a Lutheran, so I go to an Lutheran church on Sunday, but I also use the common infrastructure at other times”), just as much as people who only use the common one.

(3) Democraticness — That fact that our common honoring infrastructure belongs to us all should be reflected in how it is governed. A democratic form of governance best embodies the liberal concern for equal human dignity, as each person should have some kind of say in the decisions that affect their lives, including when those decisions are about their polity’s common honoring infrastructure. Of course, democratic governance can take many creative shapes and forms, and the best way to democratically govern a common honoring infrastructure will probably look unconventional.

These principles, which all arise from the respect for the equal and inherent moral dignity of every person, define at least some25 of the limiting parameters for a common honoring infrastructure that is legitimate in our liberal order. Within these limiting parameters, there is infinite possibility-space for a common honoring infrastructure that is just as rich, beautiful, and fulfilling as any of the non-liberal ones that have come before—which we’ll now explore.

VI. Envisioning the Contemplarium

Within the generous parameters above, how might we build a legitimate common honoring infrastructure that is also rich, beautiful, and fulfilling? One that rises to the privilege of helping us honor ourselves and those around us?

The Contemplarium is one stab at answering that challenge.26

What is the Contemplarium? In short, it is an institution that builds and supports legitimate, common honoring infrastructure for local polities.27 We can call it a “common honoring institution” for short.

The goal of the Contemplarium is to support honoring of the human journey for (1) the local polity as a whole (“the public”), and for (2) private individuals, groups, or communities within the local polity. The Contemplarium does so by developing, maintaining, and offering institutional support, tools/technologies, and skills for honoring—in the form of (a) physical offerings, (b) programming, (c) capacity-building, and (d) professional services.

Here’s a summary of what the Contemplarium does, with illustrative examples I have in mind as starting points. All of the following are intended to paint the picture of what a Contemplarium could look like, to inspire with specifics—but this is not meant to limit the imagination for how else the Contemplarium could serve as a common honoring institution.

Let’s dive into each of these in turn.

(a) Programming

As a common honoring institution, the Contemplarium uses Programming to offer opportunities for members of the public to honor each others’ (and their own) individual human journeys in structured, synchronous ways:

A thematic calendar, the “Common Year”, serves as a tool to chronologically scaffold all the Programming above by marking out macroscopic themes common to our human journeys—questions that come up in many of our most critical experiences of life. Because these themes are on a shared, common calendar for the public, they offer the occasion for the public to honor and explore these parts of the human journey together:

(Footnote from Table 3: “death, isolation, freedom, meaninglessness”28)

For a given local polity, this calendar can also honor the human journey through tying in nature-based metaphors from the local floral and fauna.

For private entities, the Contemplarium can potentially also host versions of this Programming for a smaller group or community (though this lacks publicness, which is the main point of the programming). However, the Common Year can definitely be used by private individuals who want to honor their own human journeys in a more structured way.

Through this Programming, the Contemplarium builds the common honoring infrastructure by providing institutional support to develop and put on this programming; by developing tools/technologies in the form of the methodologies behind Journey Groups and Monthly Reflection Jams, as well as the chronological tool of the Common Year; and by building the honoring skills of deep listening, recognizing moments for honoring, abiding with the themes of the human journey, and so on.

(b) Physical Offerings

As with Programming, the Contemplarium uses Physical Offerings to offer opportunities for members of the public to honor each others’ (and their own) individual human journeys in structured ways—but asynchronously.

This involves technologies that enable honoring to happen in public spaces—as windmills harvest the energy of the wind to be redirected and used for work, so honoring technologies collect the honoring power of the local polity to be directed at the experiences which are owed it. These are intentionally designed not as art (an expression of the artist) but as utilities (of use to the community), where every user interaction is in service of enacting honoring. Some of these technologies set up for the public include:

(Footnote from Table 4: “community”29)

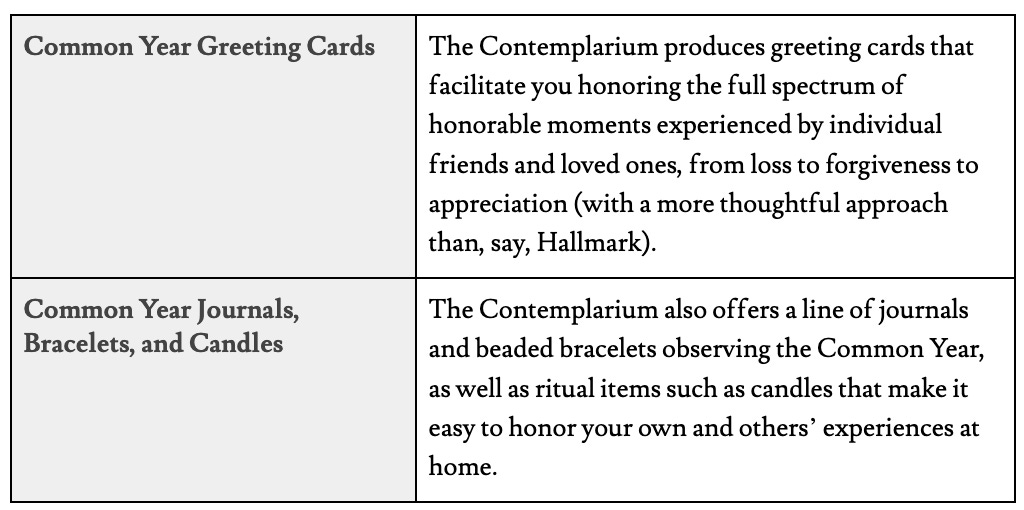

The Contemplarium also offers some tools to honor the common human journey more privately. For private communities, some of the technologies above can be implemented and adapted for those private communities. For individuals, the Contemplarium offers:

The Contemplarium also offers public physical spaces to the community—contemplative “third places”. These spaces host the physical offerings described above, provide various spaces to host different kinds of programming, and also offer a peaceful sanctuary to hold people as they contemplate their own human journeys and honor them silently through analogues to prayer. Inside, these physical spaces combines the calm of a college campus chapel with the numinosity of the Temple at Burning Man. When you step inside, you know right away that your human experience is being held in beauty, in care, and in awe.

Ultimately, the Contemplarium buildings themselves have an “existence value” of their own. They serve as beacons in the polity, sending the message that “honoring is important; we are a people who honor”:

Through Physical Offerings, the Contemplarium builds the common honoring infrastructure by offering institutional support that creates and maintains the tools/technologies above. These technologies facilitate key honoring skills that are developed by the public as they use them.

(c) Capacity-Building

While Programming and Physical Offerings are important ways to scale the enacting of honoring across a local polity, much of our honoring still has to take place directly, person-to-person. As the examples at the beginning of this essay illustrate, there are myriad ways our everyday interpersonal interactions are naturally infused with honoring—we do it all the time, subconsciously even.

Pervasive as it is, honoring sometimes doesn’t come easily or naturally. In fact, I believe that honoring is a set of skills that we learn. Sometimes we lose practice or lose facility with certain of these skills, or sometimes we’re unsure how to apply these skills in new or challenging situations. Some of these skills broadly break into three categories, but in most instances they are deployed in combination, as appropriate for the context:30

(Footnotes from Table 7: “ritual … decency”31, “counsel”32)

The Contemplarium aims to build the capacity of everyone in its local polity to develop and use the above skills in their daily lives—at home, at work, and in public. These skills build up to a critical mass in the local polity, such that the polity—as a people who honor—honors itself.

Some ways this capacity-building happens is through these mechanisms:

(d) Professional Services

In our local polity, we all owe each other honoring. However, we can’t always do this directly, person-to-person, even in forms facilitated by technology. There are moments when somebody may be experiencing an important part of the human journey, but honoring that moment may, in fact, be inappropriate for normal people in the polity. For example:

When that crucial moment requires specialized skill and sensitivity—e.g. when someone is particularly vulnerable, or when it’s a particularly momentous occasion.

When it’s not structurally feasible for informal honoring to happen among the general people in the polity—e.g. when privacy or confidentiality needs to be structurally guaranteed.

When the honoring that is due would put an undue burden among the general people in the polity—e.g. when dedicated time and emotional capacity are needed to honor particularly weighty experiences.

So in these moments, we encharge dedicated “honoring professionals” to honor on the polity’s behalf.33 The Contemplarium employs and makes these honoring professionals available to the polity.

The role of honoring professionals is to represent and enact the polity’s honoring when direct honoring is not appropriate, as illustrated in the examples above. To do this, honoring professionals share certain features:

(1) Specialized skill and sensitivity — As a result of extensive, rigorous training, honoring professionals demonstrate high competence in the skills of Accompaniment, Ritual, and Counsel. (See Table 9 below.)

(2) Structural confidentiality and omnipartiality34 — Through whatever structural arrangements necessary (legal, institutional, professional, social), honoring professionals are bound to guarantee confidentiality. They are also structurally bound to act omnipartiality—they are tasked with finding and uplifting the equal and inherent human dignity of everyone in the polity. Furthermore, as agents of the Contemplarium, they belong to an institution that is independent, insofar as it is ultimately accountable only to the local polity and to the commitment to equal and inherent human dignity, and are not involved in any formal legal or punitive processes.35

(3) Sustaining a dedicated role — As dedicated practitioners, honoring professionals are obligated to nourish and sustain their own hearts and spirits. Part of their professional practice is to grow in emotional and spiritual strength and maturity. As healthcare workers are required to wear personal protective equipment, honoring professionals invest in their own self-cultivation so that the local polity can be confident in relying on them to sustain their important work.

Because they have these features, honoring professionals are able to bring the honoring of the polity into moments that might otherwise be unreachable. Corresponding to the skills in Table 7 above, below are some of the ways that professional honoring manifests, with reference to existing professions that exemplify those skills today. Different honoring professionals may have specific specializations, but, because honoring often requires a mix of these, all honoring professionals should have facility in each skill:

There are two advantages to having honoring professionals with these particular skills work under the institutional auspices of the Contemplarium:

(1) Appropriate availability — First, the Contemplarium provides consistent institutional support to ensure the availability of these honoring professionals to the local polity at the moments that need it, by hiring, preparing, and deploying them appropriately. The Contemplarium also builds service delivery structures that make sense for different contexts: e.g. an honoring service for a hospital, or an ombuds support service for local private communities. In such a way, the local polity as a whole is ensured access to these services everywhere it matters, rather than simply in the institutions that choose to build them separately.

(2) Quality assurance — Most importantly, the Contemplarium helps ensure a consistent, high quality standard that allows the local polity to trust the work of its honoring professionals. Because an honoring professional is a representative of the local polity, they owe the polity (as both honorant and beneficiary) a job well done—that is, work that is both skillful and consistent with the commitment to equal and inherent human dignity. The Contemplarium thus provides both professional training and professional accountability that differentiate its practitioners from others that might be on the unregulated, open marketplace.

Because of their honoring skillset, honoring professionals also play a key role in creating, designing, and offering the Programming, Physical Offerings, and Capacity-Building described above. Likewise, they are vital to building and maintaining the Contemplarium as an effective, purposeful honoring institution.

Honoring professionals also have “existence value” in much the same way that the physical edifices of the Contemplarium do: even when they are not being “used”, their presence and availability is a beacon of the importance of honoring among the local polity.36

There is a limit to what honoring professionals do. For example, healthcare and mental healthcare, therapy, long-term intensive support, and other kinds of services may often be necessary in and around situations that honoring professionals are involved in, but they are out of their scope of practice. In these situations, the Contemplarium maintains vetted referral networks connecting to effective and trustworthy service providers who align with the values of the Contemplarium.

The Contemplarium’s Programming, Physical Offerings, Capacity-Building, and Professional Services complement and synergize with each other in powerful ways. Together, they reweave a broad-based honoring infrastructure that breathes humanity into the local polity.

I’ve depicted a lot of possibilities here—my purpose was to paint the possibility space with as wide a brush as possible, to show the fullest potential shape of vision for the Contemplarium with enough tangible details to give it color. But I mean this entire sketch to be a starting place, one from which to start asking questions more than providing an answer. For us to build a truly effective Contemplarium, these and manifold more ideas will be riffed on, experimented with, tested, and improved upon over time.

Nevertheless, I hope I’ve shown that all of the possibilities are in service of one purpose: rebuilding our common honoring infrastructure. For everything we test, we should rightly bring it back to the question: How does this activity or program or tool help us honor inherent and equal human dignity in our local polity? When we understand our purpose and our constraints, the possibilities within are endless.

VII. An invitation

So when I talk about the Contemplarium, what I’m talking about is rebuilding our common infrastructure to honor our human journey. That’s what I truly care about—what I’ve sought to learn how to do for much of my adult life, through work in conflict resolution, chaplaincy, philosophy, and ministry. It’s why I’m drawn to temples and hospitals and other public honoring spaces, and why I find it so fulfilling to learn the profound art of honoring in many different contexts. It’s what I have dedicated, and will continue to dedicate, my life to.37

I don’t expect everyone to care about honoring the way I do. In fact, I think a good number of people are fine with a world where this kind of honoring is missing. But over the years, I’ve come to understand that many people—if not most—yearn in their hearts for the kind of honoring our society has come to neglect.

And so, I extend an invitation—to anyone for whom this need for honoring resonates. To anyone who has felt the weight of those ineffable moments of our human journey. To anyone who has paused in those liminal moments and in-between spaces. To anyone who wonders at the curious flutters of the heart, the spirit, the conscience, who has experienced the power of a listening ear, a time-tested ritual, a wise word. To the artists, the builders, the poets. To the liturgists, the naturalists, the chaplains. To the philosophers, the peacemakers, the guiding voices. To the patrons and protectors of the arts and of nature and of all the beautiful things that uplift our society.

I invite us to build together. To nurture something so perfectly use-less, yet so perfectly necessary for a life well-lived, for a society well-ordered. To make good on what we owe each other, simply as humans in relationship with the humans who surround us. To join the visionary framers of our liberal order, the tireless weavers of our civic fabric, and the radical guardians of our ever-evolving legacy—in bringing us one step closer to becoming, at last, a society of equals, a kingdom of ends38, a people who realize the fullest extent of our dignity—

A people who honor.

Will you join me?39

Next steps

🛠 We are building the San Francisco Contemplarium, an instance of the Contemplarium in SF. If you want to help us build in San Francisco, head over to our website to follow along, sign up to build or participate, and more:

🌱 Also, I’ll be writing more about these ideas here on this ideas blog, Moral Infrastructure. If you want to follow my intellectual journey as I expand on the ideas presented here, please subscribe here and follow me on Twitter @moral_infra :)

About Seanan Fong

As a minister turned designer, Seanan combines a grounded empathy and constructive imagination to reweave our missing moral infrastructure. He is launching the SF Contemplarium with support from the Mira Fellowship and the Hinckley Fund.

Seanan received his B.A. in Philosophy from Stanford University and his M.Div. from Harvard Divinity School. Having grown up as a nonreligious Chinese American, he co-authored Family Sacrifices: The Ethics and Worldviews of Chinese Americans (Oxford University Press, 2019), a sociological study of Chinese Americans reviewed in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion as “a must-read for scholars interested in reevaluating what is, and what is not, religious.”

Bringing his perspective as a queer, secular-humanist Chinese American to Unitarian Universalism, Seanan was ordained at the First Parish in Cambridge, where he also served his parish internship. He did his clinical chaplaincy internship at Stanford Hospital, serving the emotional and spiritual needs of a wide variety of patients and their families across the theological spectrum.

As a conflict resolution practitioner, Seanan was contracted as the independent ombuds at a major technology company. He has also served as a facilitator, mediator, conflict coach, and conflict skills trainer for a range of groups navigating conflict. His work with the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program assessing a townwide political tension was covered in the Boston Globe.

Most recently, Seanan spearheaded designing UX for clinicians at a healthcare technology company serving primary care physicians. His work designing for healthcare has immersed him in the difficult structural and personal dimensions of promoting well-being in our communities.

I’m working out the kinks in these ideas, but, in the spirit of “thinking in public,” this essay-manifesto represents the arc of my thinking so far—the first time I’m laying out, in a comprehensively honest, first-principles–style, top-to-bottom way, why I think the Contemplarium is important and want it to exist. My purpose in sharing it now is to inspire, invite, and align co-creators in this work. I’m “coming out,” in a way, with some of my core convictions, and I look forward to engaging them with the wider world. It’s more important for me to put a first stab out into the world than for everything in here to be perfect, so expect iterations over time.

There are other objects of honoring that I think are important too—e.g. honoring people, honoring relationships, honoring principles—but in this essay I will focus on the honoring of people’s experiences, or as I explain later, the honoring of the equal and inherent dignity of human beings on the occasion of their experiences, or by virtue of their experiencing. I hope to fine-tune the conceptual analysis of “honoring” and its objects in future writing.

I use the term “experiencing” as opposed to “experience” because I’m intending to honor not the fact that something happened, but rather the fact of the subject’s experiencing itself, which is what indeed constitutes the subject itself (“I experience, therefore I am”). That subjectivity is what calls forth our intersubjective, relational recognition, which compels us to regard the other as intrinsically and equally worthy. See next footnote.

This paragraph is intended to have the force of poetic truth along the lines of Martin Buber’s “I-thou relation” and Harry Hay’s “Subject-SUBJECT consciousness”. However, I also intend for it to be consistent with rational truth—you might recognize the vaguest outlines of a Kantian, transcendental-style metanormative understanding of the honoring of our human journey, which I hope to explore in future writing.

And when we don’t honor our human journey, I think we sustain a sort of moral injury. I hope to explore this idea in future writing.

Sometimes I’ll use the term “honoring system” to mean approximately the same thing (at least for now).

I want to be fully transparent: the following accounts are intentionally broad-brushed, armchair versions of “history”. Indeed, think of all the “history” in this essay more as poetically licensed stories that illustrate the concept at hand using a point of reference readers will likely share, rather than as truly historical accounts. (I could just as well use, say, the history of Tolkien’s Middle Earth to illustrate the same points.) Note also that I happen to use the “history” of the so-called “West” (see also Footnote 8) as an accessible touchpoint, but it goes without saying that non-Western examples provide illustrative histories as well. In fact, I think honoring infrastructures outside the “West” illuminate a lot of what is hard to see from our perspective—for example, I think I only have come to many of the views in this essay only due to my study of East Asian traditions, Confucianism, and the values of Chinese Americans (particularly in my exploration of the concept of liyi 禮義). I hope to explore all this and more in future writing.

The so-called “West” is a notion that deserves complication and criticism, but I’m using the term in this essay as a starting point that is familiar to most readers. The same applies to the concepts of “Christendom”, “Catholic Europe”, “liberalism”, and, for that matter, any proper nouns that appear in this essay.

My own ministerial and professional formation and credentialing happens under the auspices of a modern-day genealogical descendent of Congregationalism: Unitarian Universalism. (I’m an ordained Unitarian Universalist minister.) I hope to explore the relationship of the Unitarian Universalist tradition to the ideas in this essay in future writing.

In short, using coercive state power to impose an honoring system violates respect for human dignity, is ineffective and self-defeating, and also leads to a lot of bad consequences. I hope to explore this in more detail in future writing.

“Christonormative” is a word I learned at Harvard Divinity School to describe the indelibly Christianity-dominated culture that we as a matter of fact live in.

Note Robert Bellah’s research on “civil religion”. Of course, following the concepts laid out in this essay, the name “civil religion” reverses the way I’d describe things. Under my ontology, “religion” translates to “honoring infrastructure tied to ideology and membership requirements” (i.e. Christianity-shaped systems), and “civil religion” is simply “common honoring infrastructure (tied to ideology and membership only to the extent that these are already shared by a given polity)”. I hope to explore this more in future writing.

I’m using “liberalism” and “liberal” throughout this essay in the sense that refers to the intellectual underpinnings of a liberal democratic society, as opposed to “liberalism” as a contemporary center-left political ideology, or “liberalism” as a set of economic policies (as in “Neoliberalism”), or “liberalism” as a term for the socially progressive side of the culture wars. “Liberalism” in this broader sense includes the diverse mainline liberal tradition of thought.

I use “human being” and “person” interchangeably in this essay; let’s suppose they mean the same thing.

The inherent moral dignity of every human being is so widely and fundamentally accepted as true now, but it was radical in a time when the institutions of monarchy, aristocratic nobility, serfdom, and of course slavery were entrenched as the seemingly immovable “way things were”. In fact, it is evidence of the completeness and thoroughness of liberalism’s victory as our aspirational ideology that it’s the rhetorical water in which we swim (and take for granted, at our peril).

By the way, the core idea of liberalism—the moral dignity of every human being—is rooted in the same fundamental insight as what the thinkers in Footnote 4 were getting at, so you can perhaps anticipate the natural connection I’m about to make between honoring and liberalism in the remainder of this section.

There are many reasons the liberal project has missed or underemphasized the interpersonal dimension entailed by a belief in the inherent moral dignity of every human being. I think one of them has to do with the complicated history of the separation of church and state in the Christonormative West, which has made Western liberal thinkers contemplating the political dimensions of liberalism approach the interpersonal dimension—understandably—with reluctance. I hope that disentangling belief and belonging from honoring practices, as I’ve done in this essay, helps us think about the interpersonal dimension with more confidence. I hope to explore this more in future writing.

“Interpersonal” might also be substituted for the term “intersubjective” as well, in resonance with Footnote 3.

Some people point to the fact that the liberal project has so far failed to address our interpersonal dimension as evidence that liberalism has failed and, therefore, should be abandoned. But to the contrary, I think the very fact that we feel the absence of interpersonal honoring is evidence that liberalism itself—the commitment to the equal and inherent dignity of every human being—is the reason we even care in the first place. It’s only with our liberal sensibilities in our liberal world that we recognize that we should be relating to our a fellow polity members in a deeper, subject-to-subject way. To abandon liberalism is to also abandon the motivation for those concerns in the first place. So I say: let’s finish the job and realize a “more perfect” liberal project, not scrap it altogether. (One might claim that the commitment to the equal and inherent dignity of human beings predates liberalism—and I do think it has showed up in different forms in many traditions, but the comprehensive and supreme commitment to it is uniquely liberal.) I hope to explore these ideas more in future writing.

An alternative word to “common” that I have used is “public”, but I have found that is too easy to confuse with “state-run”, which is definitely not what I mean.

Here in the Christonormative West, honoring infrastructure has been so tied with Christianity (and the Christianity-shaped notion of “religion”) that sometimes it’s hard to remember that you can honor without an ideology or a membership identity. Christianity happened to bundle those three things—the ticket of entry to the honoring practices of the church was ideology and membership—but such a bundling is by no means a necessary fact of the universe. Honoring came long before Christianity. I hope to explain this further in future writing.

Again, I’m using examples from the “West” as a convenient reference point that may be familiar to readers. Of course, it’s worth considering comparisons with other honoring infrastructures – such as the one in “traditional China”, and I hope to do that in future writing.

By the way, some people—like the so-called “Catholic Integralists”—do want to recreate a theocracy in a very anti-liberal way. To reiterate the point of Footnote 18, these Catholic Integralists might see some things lacking from our society, but pursuing an anti-liberal solution to solve that is not the way to go.

You’ll notice these features describe the opposite of a cult – and indeed, a liberal honoring infrastructure should work as a force against cults. What makes a cult are a set of anti-liberal characteristics: subordination of individual choice to that of the group and making the cost of leaving extremely high (opposite of voluntariness / respect for autonomy), all-or-nothing totalizing thinking and use of thought-terminating cliches (opposite of pluralism), disempowering ideologies (opposite of respect for dignity), and autocratic leadership and status hierarchies (opposite of democraticness). Cults also take religious belief and belonging to the extreme, with totalizing creedal requirements and requirements of isolation from the broader polity – opposites of being “common” as defined above.

For example, see the political theology of the Catholic Integralists, one among many anti-liberal challenges—traditionalist and radicalist, indeed from all ideological directions—confronting liberalism today.

Some cults, for example, will make the cost of leaving the group extremely high, such as cutting off all social connection with members if you decide to leave. This violates voluntariness.

There might be additional parameters worth considering in more detail. A legitimate common honoring infrastructure should have, for example, institutions that respect due process rights.

I’ll answer the question “Why the name ‘Contemplarium’?” in future writing. In short, the word “contemplation” comes from the Latin “to look at” or “to mark out a space for observation”, which evokes an honoring space that allows people to bear witness to and hold human experiences. Empirically, the name has also evoked a unique combination of welcome, whimsy, and seriousness that has proved useful for communicating the intended vibe of this institution.

I wrote this essay to be able to give this true, complete definition.

The first four of these are Irvin Yalom’s four existential concerns.

I’m starting to use “community” interchangeably with “local polity” here. This public sense is one of the ways I think we commonly use “community”, so I do so here. The other way we use “community” is to refer to a private association of people—in those situations I will usually say “private community”.

It goes without saying that I’m going to write more about these skills in future writing, so please subscribe to this newsletter :)

I’m really talking here about the Chinese concept of li 禮, translated as “ritual” or “ritual propriety”, which runs the gamut from everyday etiquette to formal imperial ceremonies. This way of carving the conceptual space is very apt and useful for our understanding of honoring.

“Counsel” is a tentative term. I hesitate to use it for fear of people interpreting it as a top-down moral authority, wagging a holier-than-thou finger at you. That’s not at all what I intend. What I intend is something more like “moral accompaniment”, talking something through with someone and bouncing your thinking off of them—as you would ask of a friend whose good judgment you trust. Your conscience remains the decision-maker; the moral accompanier is there to support your conscience—and gently question it—to help it discern a thought-through conclusion.

At the same time, this counsel comes from an “emic” perspective—it’s from someone in the ring with you who shares and internalizes the moral stakes, not someone who tries to therapize you or just make you feel better about yourself. Consider, for example, what people are looking for when they post on an AITA (“Am I the asshole?”) subreddit, or write into Anthony Kwame Appiah’s The Ethicist column, Philip Galanes’ Social Q’s column, or Roxane Gay’s Work Friend column. With moral accompaniment, I simply imagine a more dialogical partnering process rather than a one-way written response. This process helps the asker’s conscience feel, reason, and weigh its way through the issue, guided by the liberal ethical principles that we generally share. Doing that well is the skill I hope to see more of in our world.

Hopefully it’s obvious I’m not talking about legal counsel—I’m talking about what we might term “moral” counsel, which is part of the honoring system, not the legal system. I am also not talking about therapy, nor counseling, which have purposes such as healing, treatment, or problem-solving that are quite distinct from honoring. I will explore this distinction more in future writing.

Another name for the “honoring professions” might be what I might call “secular ministry”—I think we benefit from thinking of those as part of one professional lineage. By way of analogy: Physicians of medieval and early modern times used to have all sorts of beliefs that in later times were no longer commonly shared, and their practice was wildly different because it was based on those beliefs, but we still called their successors physicians because their purpose—healing—hadn’t changed. Likewise, even if the new practice of professional honoring doesn’t necessarily involve supernatural beliefs, I think we can still call these practitioners “ministers” if we focus on their constant purpose—honoring—which also hasn’t changed (at least in my account of things). I hope to explore this more about this in future writing.

Omnipartiality is a concept I learned from conflict resolution work that describes a bias in favor of all parties, in contrast to the somewhat unattainable notion of “impartiality”, a lack of bias for anyone. Omnipartiality is an especially appropriate concept for honoring practitioners because they are consciously tasked to honor the equal and inherent dignity of every person.

These structural considerations are based on the Standards of Practice for organizational ombudses: Confidentiality, Impartiality, Independence, and Informality. These are transferable to the role that honoring professionals should play.

My friend, a nurse, described a time she felt herself light up with joy and appreciation when a chaplain showed up on her floor—not because the chaplain did anything particularly noteworthy, but because that chaplain’s presence simply made my friend remember that people exist in our world who do what chaplains do.

I’ll share more about my own biographical journey toward this calling in future writing.

To borrow Kant’s term.

I want to gratefully acknowledge my friend Joshua Leach for his steadfast thought-partnership on these and many other matters through the years, without which these ideas would not have developed. Moral and intellectual friendship has been one of the most fulfilling aspects of my own human journey.

Truly appreciate this helpful framework. You're doing a brave thing by creating a place for people to honor. 👏