Introducing a Common Ritual Calendar

A proposed schema for the Contemplarium’s Common Year (v1)

As we wrap up our launch month over at the SF Contemplarium, one key takeaway has been the level of intrigue and interest in the Contemplarium’s “Common Year”, a ritual calendar that gives narrative shape and symbolic meaning to the seasons of the year.

To be honest, this has been a bit of a surprise. I know I myself love the idea of a liturgical calendar, but I wasn’t sure how it would land for folks outside my circle of enthusiasts as I introduced it in bits and pieces last month.1 But I was pleased to hear people wanting more of the seasonal narrative I’ve begun to offer, and asking me to lean into the storytelling and worldbuilding of the calendar.

So, having validated some amount of real-world interest, I’ve decided to invest effort into the ritual calendar for the Contemplarium. This isn’t my first attempt at developing a secular ritual calendar: Over more than a decade, from Divinity School onwards, I’ve worked alone as well as with colleagues2 on variations of such, diving deep into cross-cultural calendrics, liturgy, and philosophy and spending far too much time wrangling color-coded spreadsheets.

For this latest project, I’ve taken the opportunity to incorporate learnings from those past efforts, as well as some new practical insights from trying to apply it to the present situation, to present a new schema that will be the starting point for new rounds of real-world testing, iteration, and elaboration through the SF Contemplarium.

Table of Contents

Introduction

What is a ritual calendar? A ritual calendar, or liturgical year, is a cycle of seasons and holidays (“holy days”) that mark the observance of themes and traditions in a community. Around the world, the sequence of traditional holidays gives a rhythm to the year, offering those observing them a chance to reflect on themes of the human experience over time.

One example is the Christian liturgical year. Based on the life of Christ, it features two main stretches of time: an anticipatory season of Advent that leads to Christ’s birth at Christmas, and an anticipatory season of Lent that leads to Christ’s death and resurrection at Easter. Filling the gap between these stretches are seasons of ordinary time. The structure of this cycle shapes the rituals, readings, and activities of Christian churches throughout the year.

Here, we are trying to craft a secular ritual calendar that serves the purposes of the Contemplarium. We’re calling it the Common Year calendar.

Purposes

Recall that the overarching purpose of the Contemplarium is to create space in the city to honor our human experiences. Corollarily, the purpose of the Contemplarium’s ritual calendar is to help create such space in time. This demarcated time-space serves to …

Provide prompts to honor our human journey. By designating stretches of time with themes of the human journey, you are regularly prompted to give those experiences the attention and care they deserve. It’s a useful tool to make honoring your and your neighbors’ experiences happen. Just as popping up a Reflection Stand in a park creates a physical occasion for honoring, a ritual calendar creates a chronological occasion for honoring—both are examples of honoring technologies developed and offered by the Contemplarium to achieve its purpose.

Ensure broad coverage of honoring themes. Whether you observe a ritual calendar with a group or go it alone, the advantage of following a systematic, well-crafted calendar is that you know you’ll get a balanced diet of honoring—you’ll get your daily recommended intake of important human themes over time. That’s something that’s hard to get when you’re building your honoring curriculum ad-hoc.

Deepen practice year-over-year. With a calendar whose themes you return to consistently year after year, you get to enrich old themes with new experiences, layering novel insights onto a lifetime of experiences. It’s rare in our society to practice something over a truly long time-frame: this gives us a chance to do that.

Synchronize the community. When your community observes a ritual calendar, you know you’re not alone in your honoring practice. It becomes easier to honor a certain aspect of human life when you know others around you are also in that heartspace. There are logistical benefits as well: Organizations like the Contemplarium can create predictable, consistent programming with automatic visibility over the next weeks and months, making it much easier to plan and remember everything that’s going on.

Enact honoring in itself. Naming a season after, say, the experience of “flourishing” is itself an honoring of that human experience writ large. By adopting the ritual calendar, the Contemplarium community is holding up the experiences named by it and declaring, “These human experiences matter. Every part of the human journey matters—so much so that we’ve dedicated each of these seasons in their honor.”

Design Principles

These are the principles that should guide the crafting of a ritual calendar appropriate to the Contemplarium. The Contemplarium’s Common Year should be …

Secular. The calendar should be secular in the sense that it is for the public, not for a private sect or association—it should be available to serve anyone regardless of religious belief or belonging. So its themes should be broadly compatible with folks who practice any kind of faith or non-faith (as consistent with liberal values) in our pluralistic society.

But also, in a way, sacred. The calendar should also be sacred in that it is set apart from the mundane rhythms of fiscal quarters, half-years, and the humdrum of a life unexamined. While the Christian liturgical calendar looks to the life of Christ to furnish its counter-cultural narrative, the Contemplarium’s ritual calendar instead looks to the human journey and the natural world for inspiration.

Locally relevant. For a ritual calendar to be successful, it has to be relevant to the community—it has to be speak to the rhythms they feel in the world around them. My hypothesis is that this relevance will come from paying attention to (1) the rhythms of the local natural world—i.e. in the SF Contemplarium’s case, the bioregion around the San Francisco Bay Area—and (2) the rhythms of local civic and social life—i.e. the public festivals and events broadly experienced by San Franciscans, like SF Pride.

Practical. While striving to be “set apart” and counter-cultural, a successful ritual calendar must also balance practicality. To be adopted, it must work within the constraints of busy people who exist within the demands of our society. It must also be easily implementable by an organization like the Contemplarium in the real world. (This consideration of practicality is the most empirically testable.)

Publicly reasonable, i.e. not arbitrary. This is a meta-principle. Essentially, I want to say that, while there is inevitably some subjective judgment in any decision (and the final subjective judgment falls to me), we should always try to make an objective (or inter-subjective) case for it that carefully weighs the considerations above. And as we weave the narrative of the year, we should be weaving from external touchpoints—e.g. what the wisdom of nature is telling us this season, or what the social rhythm of the city tends to pay attention to this month. Everyone should be able to evaluate the decision. There is no purely aesthetic choice. We don’t decide to do something simply because we like it—we do it for reasons we can defend to the public.

Ultimately, I believe all the principles above should result in a publicly legitimate calendar, rooted in our polity’s common reference points. A shared sense of aptness should naturally flow from that. To a San Franciscan at the SF Contemplarium, then, observing the calendar should feel like it just “makes sense” in the context of the city. It should feel like nature itself, or the social rhythm of the city, is slowly revealing its wisdom. Of course, we’ll know that effort and care went into every decision, but to a visitor, any insight from living the ritual calendar should feel like a marvelous discovery, not a contrived imposition, of meaning.

The Calendar – Part 1: Mechanics

Foundational Decisions

Some foundational architectural decisions derive from balancing the principle of being “set apart” with the principle of being practical:

Gregorian weeks and months. The Contemplarium’s ritual calendar will broadly operate on top of and derive from the Gregorian calendrical system of weeks and solar months.3

A special role for Sundays. The ritual calendar will center Sundays in the calendar, as a day particularly appropriate for public community events. We’ve learned that Sunday afternoons and early evenings are often times people are game for a bit of contemplative programming. This is undoubtedly not accidental—in the Christonormative West, Sundays were designated for church. It makes sense to reappropriate this chrono-architectural feature of the week for secular contemplation.

Being a little “set apart” in reckoning segments of time. The special role for Sundays will allow for some degree of being “set apart” from mundane Gregorian calendrics in how we reckon seasons and their subdivisions, in an elegant way that doesn’t stray too far from the beaten path. I’ll explain below when I introduce “Contemplary months”, which are four-week spans pegged to Gregorian months. (It’s less complicated than it sounds.)

Lunar aesthetics. While we set aside the use of moon cycles in the actual mechanics in our calendar, I think the moon does offer a powerful counter-cultural sensibility—as the pilot Reflection Jam demonstrated, it’s a compelling way to mark time. So I think it’s helpful for aspects of the lunar cycle to be weaved in and referenced aesthetically, as you’ll see below.

The Empty Canvas

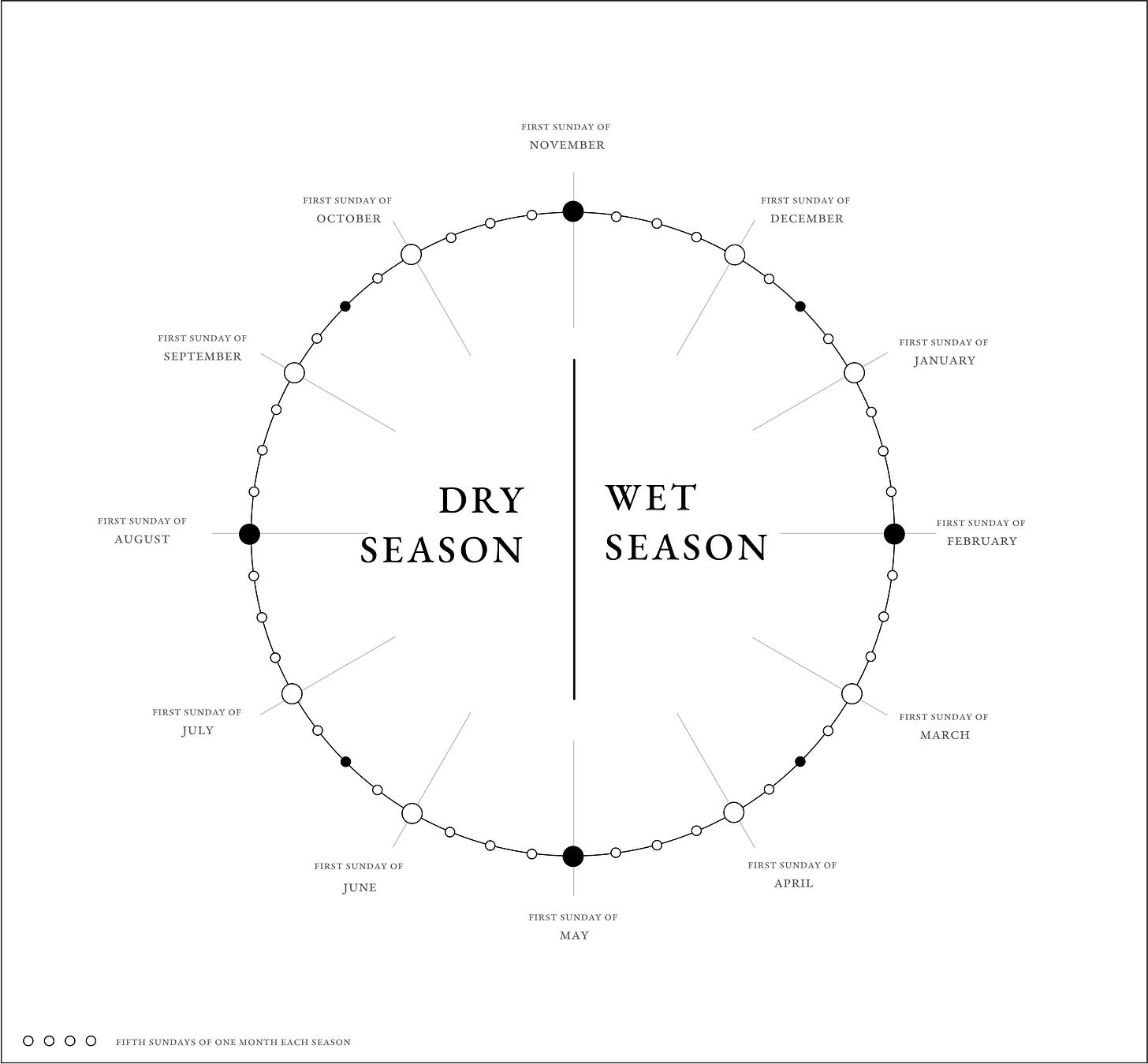

Let’s start with the schema beneath the schema: how do we want to think about what a year is made of? That is, do we primarily think of a year as being made of around 52 weeks? Or as twelve Gregorian months? Or as something else?4 For our purposes, I propose the following schematization:

In the diagram, the circle represents the year, and each dot represents a Sunday. The year is divided into twelve “Contemplary months”, i.e. periods of four weeks (or sometimes five) that start on the first Sunday of a given Gregorian month and end on the first Sunday of the next. So for example, the four-week period from the first Sunday of November to the first Sunday of December is one Contemplary month. In 2024, that spans from November 3 to October 1.5

You can think of this basically as an idealized Sunday calendar, where we consider each Sunday and the rest of the week that follows as the fundamental unit.6 The seasonal landmarks we consider from here on out will thus “round” to the nearest Sunday. This gives us a regularized, abstractified canvas that (1) is very practical for planning Sunday-based programming and (2) can be applied to any given year over time. (See the “Contemplary Months” section below for how this bears out.)

Dividing the Year into Seasons

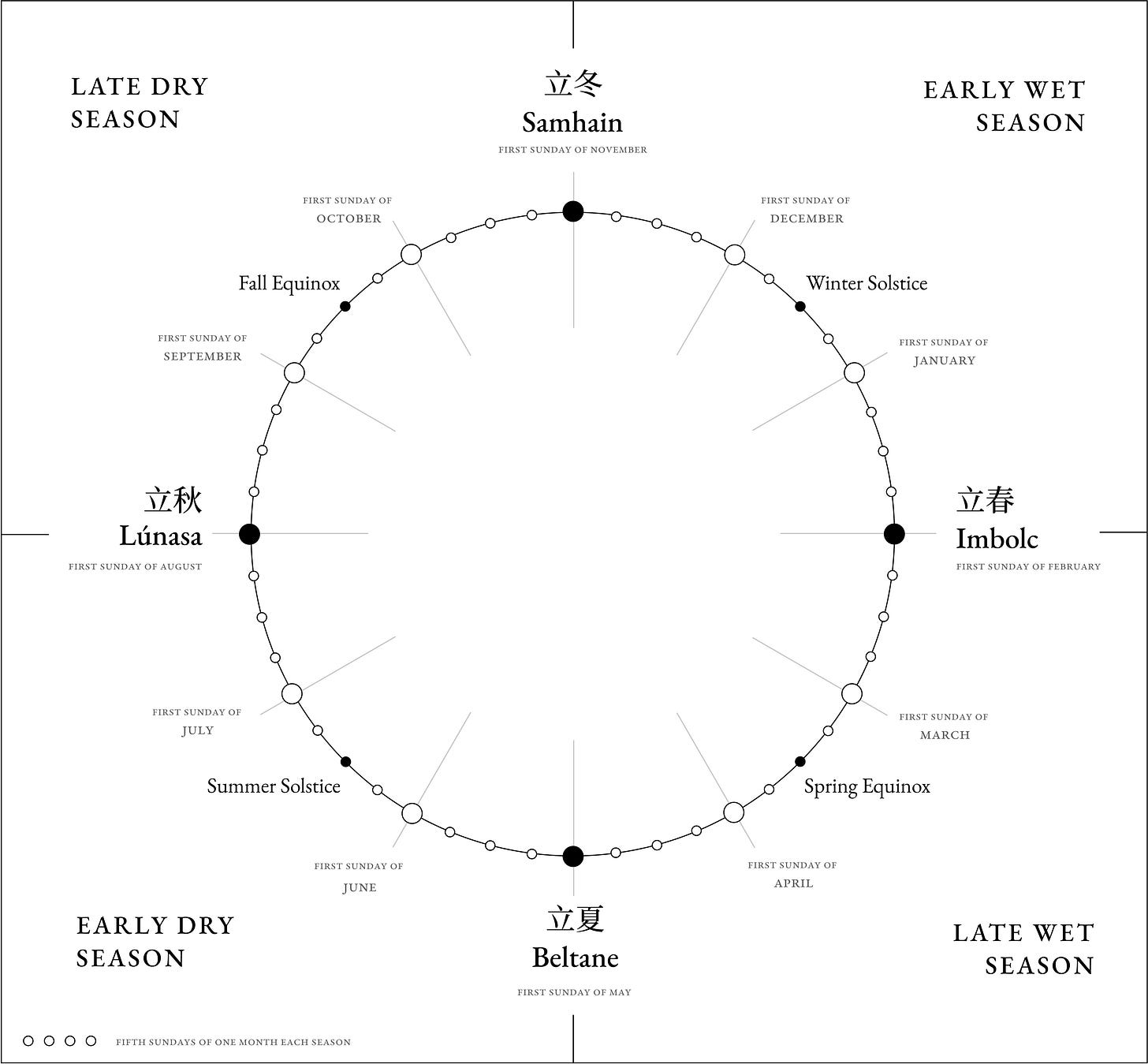

Now, how do we divide the year into seasons? Across many traditions, a very natural way to do so has been to utilize the solar seasonal landmarks: quarter days (solstices and equinoxes) and cross-quarter days (midpoints between solstices and equinoxes; I use the Gaelic and Chinese names here). Here they are mapped and rounded to the nearest Sunday:

In the Western meteorological calendar, we mark the starts of the four seasons with the equinoxes and the solstices. However, in both the Celtic and Chinese calendars, the starts of the four seasons are marked with the cross-quarter days: the Chinese names for the period surrounding these days are literally “Establishment of Winter”, “Establishment of Spring”, and so on. And under that system, the equinoxes and the solstices mark the middle, the height, of the season—hence Summer Solstice is even now known as Midsummer in English.

Growing up in the SF Bay Area, I’ve always intuitively felt more aligned with the equinoxes and solstices marking the height, not start, of the season. Recently I’ve discovered that there is a climatological basis for why. In California, we really only have two seasons, “Dry Season” and “Wet Season”. The Dry Season starts when the rains stop in May, and the Wet Season starts when the first rains fall again in November:

This ecological pattern, along with the Celtic and Chinese precedents, supports the notion that the cross-quarter days should be the ones demarcating the turn of the seasons, at least for the San Francisco—focused Contemplarium. So in my proposal, the equinoxes and solstices are de-emphasized, serving as secondary landmarks that mark the heights of the seasons to which they belong. So for our underlying architecture for the four Contemplary seasons, we get something like this:

We now have our basic outline for the year. Next, we assign meaning to this outline, in the form of themes of the human journey.

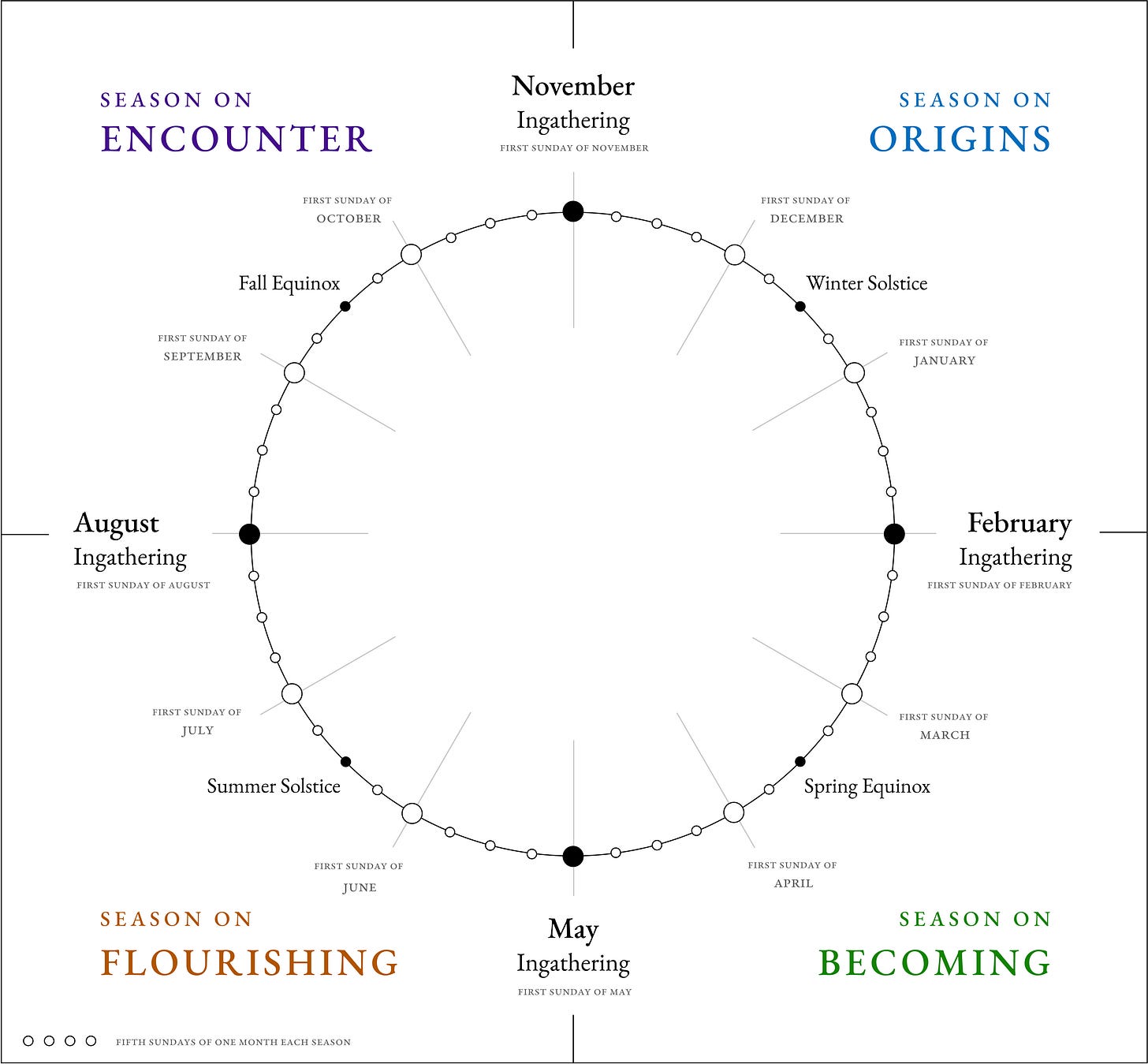

The Calendar – Part 2: Themes

Let’s correlate ritual meaning to each season. I believe that there are four overarching themes to the human journey writ large: Encounter, Origins, Becoming, and Flourishing. If we listen to our local natural world, I believe we find that each of the local climatological seasons corresponds quite well to one of those aspects of the human journey, like so:

Each season’s theme highlights foundational human concerns that we choose to accent in our honoring practices, correlating with metaphorical life stages, seasonal horticultural practices, and behavior of the local ecosystem.7 These themes represent dimensions of the human experience we honor.

Of course, in our human live we may experience all of these foundational concerns during every part of the year and at every stage in our lives, but these seasons give us gentle occasion to give each its own attention—not in an all-consuming way, just in a way that makes space for them in our experience.

Let’s now go through each in turn.

🟪 Season on Encounter: August through October

The Season on Encounter begins in August, at the start of the second half of the dry season. The landscape is marked by quiet, rest, and slowness. The local flora enters dry and golden dormancy, as this cycle of life nears its natural ending. Bright wildflowers soon transform into ripe berries, and the oaks become heavy with acorns.

This is the season where we honor our encounter with the ultimate limits of our human existence: isolation and loss, freedom and responsibility, meaninglessness and absurdity, suffering and the dark night of the soul. We acknowledge with care and respect the ever-present company of our own impermanence.8

The August Ingathering marks the beginning of this season. We celebrate the harvest and reflect on our “first fruits”—the achievements and lessons we have gathered over a season of striving. We also honor those who have retired in the past year, recognizing their contributions and transitions into a new chapter of life.

As the season progresses, we arrive at the Fall Equinox in September, a moment of balance between light and dark. Through reflection and ritual, this seasonal midpoint invites us to recognize death as part of life, and day as part of night. The season culminates in a final encounter with the endings of things, expressed through our cultural celebration of Halloween and Day of the Dead.

🟦 Season on Origins: November to January

The Season on Origins begins in November, when the first rains soak the dry earth. As the last cycle ends, a new one quietly begins. The ground awakens; seeds begin the slow, deliberate process of germination and rooting. Above, storms grow as the season progresses. Below, life reconstitutes in silence, sight unseen, gestated by dark, nurturing soil.

In this season we honor everything that makes us who we are: Our atoms, formed in stars. Our cells and tissues, working in marvelous coordination. Our instincts and histories, our relationships and responsibilities—intersections which constitute our social and psychological existence. And amidst this, something curiously more, springing from these causes and conditions: Our choice-making will, our agency, which somehow emerges through structure to give rise to a self-owned destiny.9

The November Ingathering signals the arrival of this season, the turning from an encounter with our limits to a return to our roots. As we honor those who have passed away this past year, we also remember that all of our ancestors—by blood and by spirit—continue to live on through us. Their legacies shape, for better or for worse, what we are.

A deepening appreciation of the many facets of our origin and constitution—cosmic, biological, social, historical—continues through to the Winter Solstice, the longest night of the year. It’s here that, out of the rich soil of our origins, there begins to sprout a seed—the seed of our own will, our own creative energy, a growing light emerging slowly from the darkness. Resolutions prepared for the New Year express the light of this generative force, propelling us toward rebirth.

🟩 Season on Becoming: February to April

The Season on Becoming begins with the early blooms of the manzanitas and their hummingbird friends in February. It’s time to clear the accumulation of branches felled by last season’s storms, and now the weeding and pruning, the sowing and propagating proceed in earnest. By season’s end, the hills are bursting with flowers.

This season celebrates the emergence of who we want to become. From the sprouts of our human natures, rooted in our contexts, we choose to cultivate our strengths—of wisdom, courage, humaneness, justice, moderation, transcendence, and all their kaleidoscopic varieties.10 Through continuous and careful tending, we honor these strengths as the continuous and embodied expressions of our agency.

The February Ingathering honors this new birth. As we dedicate all those who were born in the past year, we also honor the blossoming of our strengths. At the same time, we clear away that which may not serve us in our welcome of new life.

As the season progresses, hope and potential grow alongside the stirrings of warmth. By Spring Equinox, the days are growing as fast as they ever will. This is a moment to bless our commitment to growth, the foundation of a life well-lived.

🟧 Season on Flourishing: May to July

The Season on Flourishing begins in May, when the abundant wildflowers begin to yield seeds. Through the season, they set, ripen and self-sow, or are collected by foraging birds. The heat intensifies as the days grow long.

This is the season we honor the enduring pursuit of purpose and meaning, the continuous striving for a life well-lived. Through our callings—realized through the work we do, the people we care for, the battles we fight, the decisions we make, or the art we create—we shape and share our legacies.11

The May Ingathering celebrates this turn from inward growth to outward contribution. We welcome those who have come of age in the past year to the ongoing life of our community, to which we all share a responsibility. A blessing of the hands appreciates the difference each of us makes to each other.

With the day at its longest, the Summer Solstice—amidst the quick succession of celebrations from Juneteenth to SF Pride to Independence Day—marks an occasion to savor the fullness of life. During this stretch, we wish joy, warmth, and vitality upon our lives of work, play, and connection.

The Season on Flourishing concludes with the August Ingathering and the Season on Encounter, and the cycle of our seasons—and of our lives—continues.

Contemplary Months

We now have a sense of the rhythm of the year, which divides into four seasons, which each then divides into three Contemplary months. In turn, each Contemplary month divides into four weeks (or occasionally five). The advantage of how we’ve structured this these four weeks can create a steady, predictable rhythm of core Sunday activities that unfold every month.

Example Rhythm of a Contemplary Month

While this rhythm has to be worked out through trial and error, here’s an example to demonstrate how such a rhythm might go:

First Sundays: Every first Sunday is a friendly Contemplarium Tea in the afternoon, followed by a Reflection Jam in the evening. At the start of the season (first Sundays of February, May, August, and November), the Seasonal Ingathering happens instead.

Second Sundays: Every second Sunday there is a Reflection Pop-Up and an open Listening Circle, followed by an Honoring Skills Workshop.

Third Sundays: Every third Sunday is a Community Outing to volunteer or hike. At the mid-season (third Sundays of March, June, September, and December), a celebration of the Solstice or Equinox happens instead.

Fourth Sundays: Same as Second Sundays.

Occasionally Fifth Sundays: (Happens about 4 times per year.) This begins a fallow week at the Contemplarium, so Contemplarium staff have an opportunity to rest and recoup.

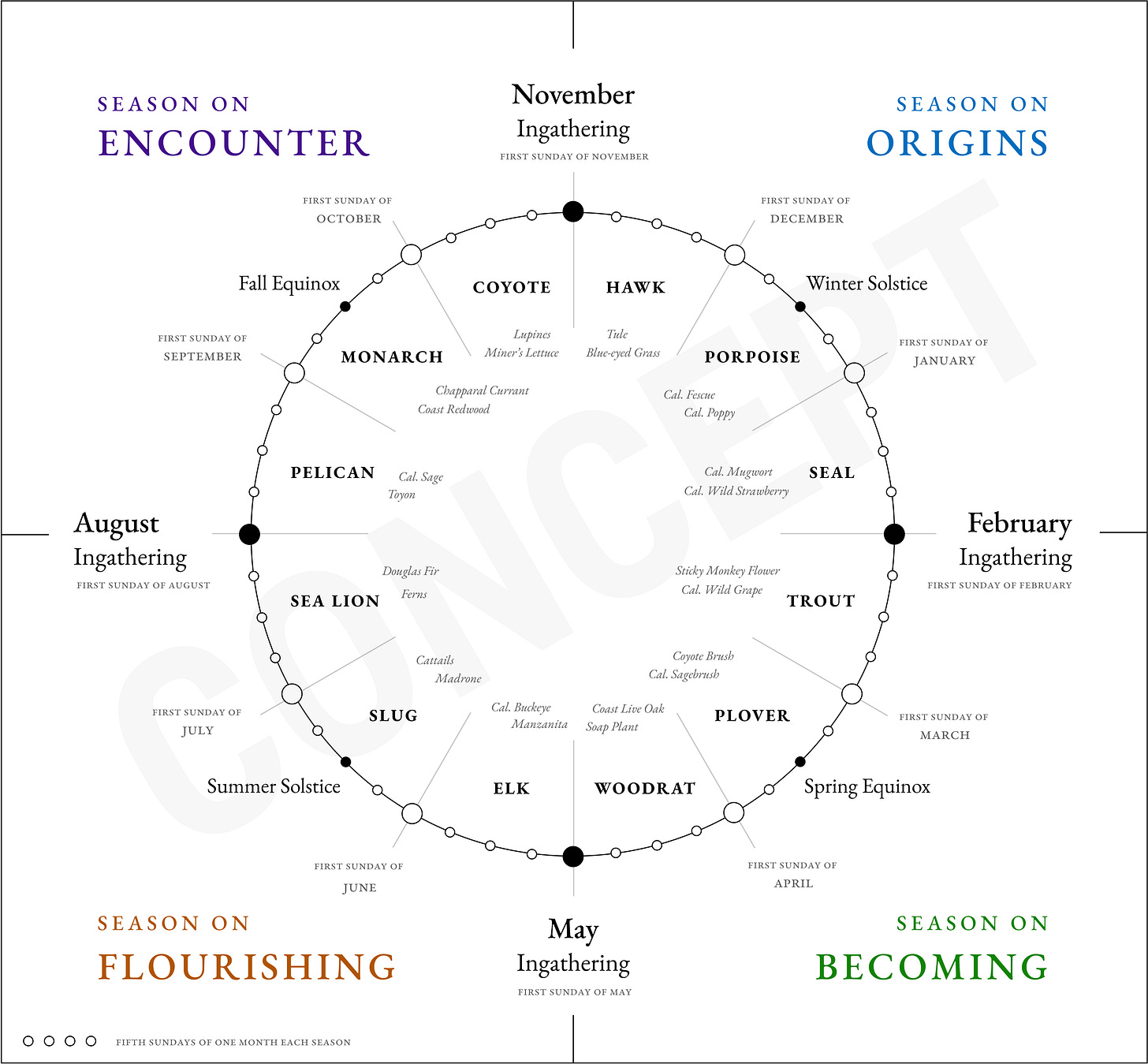

Moon Names for Each Contemplary Month: A Concept

So far, our schema has relied completely on solar seasonal landmarks to divide and mark the year. However, as mentioned in Foundational Decisions, I believe that an aesthetic evocation the lunar cycle can offer a powerful counter-cultural sensibility.

Here’s one way we might weave in a reference to the moons, and to the wisdom from nature each lunar cycle may bring. Essentially, I propose a local take on the traditional moon names of the Farmer’s Almanac. In that schema, the full moon that falls in August is called the “Sturgeon Moon”, the full moon that falls in September is called the “Corn Moon”, and so on.12

In our version, we use the Contemplary months instead of the Gregorian months, and we use fauna native to our ecosystem that are particularly visible or evocative at that time of year. So the full moon that falls in the Contemplary month between the first Sunday of August to the first Sunday of September is named, say, the “Full Pelican Moon” for the arrival of pelicans migrating from the south around this time. Next, the full moon that falls between the first Sunday of August to the first Sunday of October is named, say, the “Full Monarch Moon” for the arrival of the monarch butterflies around that time.13

Then, we might as well name each Contemplary month after the full moon that it contains, so we simply refer to that first Contemplary month as the “Pelican Moon”, the second as the “Monarch Moon”, and so on. To demonstrate this concept, I’ve arbitrarily assigned some local animals to each Contemplary month:

This way, we get a completely local way of naming the Contemplary months that evokes what is salient in our local natural world, and which can serve as a source of inspiration for our reflection.

In addition to each month having a “patron” animal, I think it would enrich the calendar to feature two “patron” indigenous plants each month whose characteristics are particularly evocative of certain virtues or strengths. For example, the Pelican Moon could be paired with with the drought-resistant Toyon plant, symbolizing resilience and perseverance, and the fragrant California Sage, symbolizing clarity and healing.

This schema of patron animals and plants would enable us to find inspiration from the natural world for a range of virtues throughout the year. As we gain a consciousness of what’s going on around us, nature itself can become an insightful guide for reflection.14

The specific examples I’ve illustrated above are merely concept placeholders. To actually assign animal names and plants to each Contemplary month, I would like to convene local Indigenous wisdom-holders, naturalists, nature writers, and other experts in an emergent process to reveal holistic, appropriate, and resonant animal and plant matchings across the months.

The Calendar Schema in Full

Put together, here are all the elements of the proposed calendar schema, with the year divided into thematic seasons, and each season divided into thematic Contemplary months:

It is my hope that this schema meets the Purposes and Design Principles outlined earlier, though that can only be confirmed by testing this calendar in the real world.

Next Steps

My plan is to use this calendar to help plan the actual events of the San Francisco Contemplarium over the next several months as an initial test of the framework. Here are some of the outcomes I expect to come from the process:

Testing practicality. I have some confidence that this calendar works in theory to cover themes of the human journey, but does it work when applied to a real community’s activities? Is it practical in context? I’m looking forward to learning where challenges and hurdles emerge in application, and testing the assumptions I’ve made from the Foundational Decisions on outward. (E.g. I’m keeping an eye on Sundays!)

Testing social relevance. Another dimension that is hard to test in vitro is whether the calendar’s themes will feel relevant in the actual seasons they occur. I have tried to relate them to the natural world’s rhythms, but they should also feel congruent with the social rhythms of the city. An initial mapping of civic and cultural holidays, as well as local San Francisco festivals, seems to indicate the seasons do match well:

However, whether this holds up as it is tested in our lived experience remains to be seen.

Learning from holders of Indigenous wisdom and other experts. I am eager to engage this first draft of a schema with a diverse range of perspectives to ensure it resonates meaningfully with our community and respects the cultural and ecological context in which we live. This initial framework is my attempt to create something that feels coherent and relevant, but I recognize there are many layers of knowledge that need to be considered.

In addition to Indigenous wisdom-holders, I am looking forward to consulting a variety of stakeholders who have deep insights into our local environment and cultural practices. Respect for the land and the traditions of those who have stewarded it for generations must be central to this project, and I value the wisdom that can only come from that lived experience.

I hope to learn from …

Holders of Indigenous Ohlone traditions

Community placemakers and observers of local social rhythms and seasonal changes

Holders of naturalistic ritual traditions (pagan, neopagan, radical faerie, and earth-based traditions from around the world, such as Chinese traditions)

Botanists, zoologists, naturalists, native gardeners, and others with expertise in native species and ecosystems

Nature writers and local poets

Experts in psychotherapy, philosophy, and religious traditions

… and others

If you know anyone in these areas or have recommendations for who might provide valuable input, I would appreciate getting connected with them.

Elaborating the Schema. With the guidance and feedback of these experts, I hope to put more flesh on the bones of this framework, particularly for hashing out some of the specifics for the patron animals and plants of the Contemplary months.

This proposed schema for a new ritual calendar is just the beginning of a humble, iterative process. By aligning our practices with the wisdom of the natural world, I hope this calendar can be a powerful technology to help us honor important parts of the human journey. This calendar is meant to be a living, breathing project—one that grows richer through collaboration and shared insights. I welcome your thoughts, feedback, and participation as we explore this path together.

So far, I’ve only teased glimpses of the Common Year—first as I introduced the start of a new season in the August newsletter, then as I introduced the concept of animal-themed moons at the first Reflection Jam. I also included a rough skeleton of the entire year in “A People Who Honor”.

I initially collaborated with Ian Caughlan to create the first version of A Humanist Year in 2013. Later, Ian took the mantle to continue developing the calendar. During the pandemic, Ian and I also convened with Miri Mogilevsky and Spencer Wharton to think through further potential developments for the calendar.

This might seem unnecessary to specify, but I extensively explored using a lunisolar system based on moon cycles adjusted for the solar seasons, akin to the Jewish or Chinese calendars. I also considered dividing the year into the 12 zodiacal sectors (Greek) or 24 solar terms (Chinese). While indeed counter-cultural, these approaches proved logistically difficult to calculate and track, while also creating unpredictable conflicts with other social calendars with recurring monthly events. Growing up completely befuddled by when Chinese holidays would seemingly randomly happen, I should have predicted as much. So the familiarity and practicality of alignment to the Gregorian system outweighs its banality.

This matters for a few considerations of practicability: (1) Sunday-based programming will happen on a weekly basis, which requires having a way to think of the year in shorter terms like weeks. (2) But seasonal programming should stretch longer, which requires a way to think in longer terms like months. (3) Additionally, we want a schema that lets us have a cycle we can easily reuse year-over-year: there should be a single diagram that we can apply just as neatly to 2025 as to 2026, 2027, and 2028. The third part is where the regular Gregorian week-and-month system lets us down. While it gives us both a shorter term and a longer term, how weeks and months line up changes from year to year. This results in frustratingly inconsistent reckoning from year to year, with much manual work and either ad-hoc judgment calls or arbitrary rules of thumb to figure out what to do with Sundays from year to year. You could also just ditch months and divide the weeks, but then you run into problems with the monthly events.

Of course, this idealized abstraction accounts for only 48 Sundays, while a year usually has 52 Sundays. In the lower left corner, I account for this by indicating four “bonus” Sundays that appear in months that have five Sundays. Which exact months they occur in changes from year to year, which is why I put them in the corner to be “distributed” depending on the year. Each corresponding Contemplary month—“Contemplary leap-months”, if I may—will therefore have 5 weeks. (A student of the Jewish or Chinese calendar might recognize this is similar to an “intercalary month”, except we’re able to distribute the intercalation evenly in a single year because we aren’t following moon phases.)

There are a couple advantages to doing it this way: First, it regularizes everything. I can now develop a rhythm of monthly programming whereby the “first Sunday” of the month is one activity, the “second Sunday” is another, and so on, while knowing that we are regularly progressing along a season. (You’ll see this bear out later.) Second, it eliminates the bumpiness of how weeks and months line up in the Gregorian calendar, allowing us to have a single diagram that applies just as well to 2025 as it does to 2026, 2027, and 2028.

I am hugely indebted to Helen Popper’s California Native Gardening: A Month-by-Month Guide (University of California Press, 2012) for an incredible introduction to the horticultural practices and ecosystem behavior for each month. I would really like to meet this author, and hope to reach out!

Among others, key intellectual resources for the Season on Encounter include insights from Existential Psychotherapy (particularly Irvin Yalom’s Existential Psychotherapy, outlining the four existential concerns of Death, Freedom, Meaninglessness, and Isolation), Buddhist traditions, and the Stoic tradition.

Among others, key intellectual resources for the Season on Origins include the Confucian tradition (relational identity), feminist theory (“the personal is political”), and social theory (“ agency and structure”).

Among others, key intellectual resources for the Season on Becoming include Humanistic and Positive Psychology (particularly Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman’s Character Strengths and Virtues), and philosophical virtue theories across cultures.

Among others, key intellectual resources for the Season on Flourishing include Humanistic and Positive Psychology (particularly Martin Seligman’s “PERMA” framework), as well as Ethics, Moral Philosophy, and the Philosophy of Action writ large.

The origins of these moon names are murky, and I don’t necessarily want to engage in nor inherit any unsavory colonialist, imperialist, and appropriative baggage that comes with it.

In the relatively rare instance that there are two full moons in one Contemplary month, the second moon will be called a “Full Blue Moon”.

I’m reminded of Chinese or Japanese poetry, where plant symbolism serves as commonly understood shorthand for the expression of human virtues. I wish our cultural vocabulary was able to interplay with the natural world in a similar way.

What a thoughtful idea—It gives us so much internal clarity )self-talk) and possible directions of how we can control certain things that are too arbitrary in our life. I will borrow this idea (of course with due credits) to plan out something that fits in my own needs, wants, and goals. Thank you.

This is such a lovely idea! I find the addition of the cross-quarter days particularly compelling because they do seem to speak to a rhythm of the year that I noticed but didn’t have words for. I also love the addition of the local flora and fauna. Already has my brain turning about how it would be similar and different here in New England!